Making friends with enemies always entails an element of risk that

the reverse might occur. In politics, that means losing allies and

supporters and perhaps even being deemed a traitor to your cause.

Although indeed risky, this is the current approach undertaken by both

Myanmar’s opposition leader Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and reformist President

U Thein Sein.

Why should these two former foes—captive and captor—become friends?

Various reasons: to rebuild the nation; avoid reversing recent tentative

reforms; reconcile the government, opposition and ethnic groups; lift

international sanctions; and win the 2015 election.

The motives of each might differ, but the more important question

concerns what the people of Myanmar will gain out of this new tactic.

The “making friends strategy” began curiously with the two publicly

praising each other. After meeting U Thein Sein for the first time in

August 2011, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi announced her belief in the

president’s sincerity.

This was heart-felt praise for the ex-general who has embarked on a

series of bold liberalization measures since taking office in March

2011. His willingness to alter electoral regulations also persuaded the

Nobel Laureate and other minority parties that boycotted the 2010

general election to rejoin the political process.

In September, while receiving the Congressional Gold Medal in the

United States, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi insisted, “We must remember that the

reform process was initiated by President U Thein Sein. I believe that

he is keen on democratic reforms.”

The president, likewise, did not miss an opportunity to congratulate

his former prisoner during an address to the UN General Assembly in New

York. “As a Myanmar citizen, I would like to congratulate her for the

honors she has received in this country in recognition of her efforts

for democracy,” he said. These words would have been unthinkable only

two years ago, and marked the first time that anyone from the

military-dominated government has officially paid tribute to the

democracy icon.

Then, with the blessing of U Thein Sein, two key ministers of the

President’s Office, U Soe Thein and U Aung Min, attended a ceremony

commemorating the 24th anniversary of the country’s pro-democracy

uprising, known as 8-8-88, in which at least 3,000 peaceful

demonstrators were gunned down by the then-junta.

The Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) MPs donated one

million kyat (US $1,150) to the organizers, the 88 Generation Students

group comprised of former political prisoners. Their gesture went some

way towards appeasing the critics of the government.

Moreover, the president and his team also reached out to ethnic armed

groups in order to agree ceasefires and invited exiled dissidents to

return home and take part in their reform process.

All parties—including opposition and government—seem to be attempting

to achieve the national reconciliation which many leaders believe is

essential for future peace, prosperity and democracy.

Three main divisions of power—obvious offspring of the former

junta—currently exist in Myanmar: the government comprised of

ex-generals, generals-turned-parliamentarians in the legislature and the

armed forces, known as the Tatmadaw.

Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and other leading democracy advocates realize

the need to tread carefully in order not to excessively antagonize this

trio. The still-dominant Tatmadaw is not yet ready to return to the

barracks. Moreover, the military continues to wield near-total power and

is able to interfere in politics at any moment, according to the

widely-condemned 2008 Constitution.

This new political order looks more challenging and complicated for

the National League for Democracy (NLD) chairwoman and the wider

dissident community.

For the past half-century, no one—including the NLD, other opposition

groups or ethnic rebel armies—has been able to free Myanmar from the

clutches of its current and former generals. Thus, having some

“reformists” emerging out of the old political order offers the best

opportunity to move forward. This is why we must welcome the forging of

new friendships, even if this involves some risk.

Friends without Benefits?

Despite her noble intentions, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s image has become tainted both internationally and domestically.

Probably in an effort not to alienate the government, she has taken a

“neutral” stand—seemingly at odds to her customary outspoken

character—and choose to be silent on sensitive issues such as the

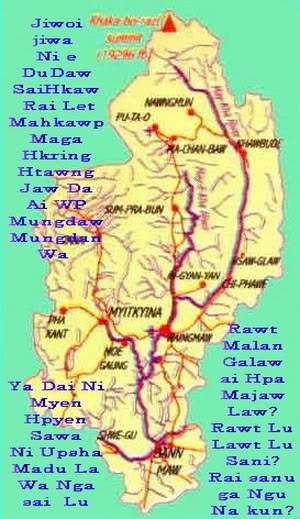

ongoing conflict between government troops and the ethnic rebel Kachin

Independence Army in northernmost Myanmar, where tens of thousands of

civilians have been forced to refugee camps by the Chinese border.

Most Kachin feel betrayed, thus costing the opposition leader the

support of many who enabled the NLD to win 73 percent of Kachin State

parliamentary seats in the annulled 1990 general election.

But that is not all. Regarding the bloody conflict between Rohingya

Muslims and Rakhine Buddhists in western Myanmar, the 67-year-old said,

“We do not want to criticize the government just for the sake of making

political capital. We want to help the government in any way possible to

bring about peace and harmony in the Rakhine State.” Again, her

“neutral” stand disappointed everyone outside Naypyitaw’s corridors of

power—the international community, the Rakhine people and the Rohingya.

The reason behind this conciliatory approach became apparent when she

said during her trip to the US, “What has happened in the past has

taught us that if we want to succeed we have to work together and the

whole future of Burma is before us,” using the country’s former name.

“If we are to ensure this future for the succeeding generations, we all

have to learn to work together.”

Having huge influence over foreign leaders, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi

advocated Western countries to lift sanctions against Myanmar—something

that U Thein Sein’s administration desperately desired while also

providing the opportunity to reintegrate into global affairs.

Understanding the important role of the powerful Tatmadaw in the

reform process, she also informally tried to befriend high-ranking

military officials in Parliament by inviting them for informal meetings

over lunch. But the top brass reportedly refused her offers, signaling

that there is still a way to go. This will be a monumental task for the

opposition leader, despite being the daughter of national hero Gen Aung

San, the founder of the Tatmadaw.

Successful or not, this pacifying political trend is highly likely to

continue until the 2015 election. As chairpersons of the NLD and the

ruling USDP respectively, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and U Thein Sein must try

to defeat each other at the upcoming ballot, despite the need to

maintain a cordial atmosphere for national reconciliation.

But how long can this last? Considering the schoolyard taunting that

characterizes the UK Parliament and the belligerent rhetoric that marred

this year’s US presidential elections, it appears that “true democracy”

requires a willingness to accept a certain amount of confrontation when

debating key issues.

Daw Aung San Suu Kyi will try to win a landslide victory for her

party as she did in 1990—if conducted freely and fairly, such an outcome

seems almost certain. On the other hand, U Thein Sein and his team will

be determined to maintain the current political structure of having

three important power holders—the government, Tatmadaw and Parliament

dominated by the military—while also maintaining an NLD presence in the

legislature for the sake of appearances.

Thus, we can assume that it is highly unlikely that the 2015 election

will be strictly free and fair. Myanmar’s next five years look likely

to be a continuation of the status quo but with the NLD and other

parties gaining more seats in the legislature.

Even if the 2008 Constitution is amended to allow Daw Aung San Suu

Kyi to take top office, the highest position she might be able to obtain

is as one of the two vice-presidents. Seeing the growing support for U

Thein Sein, both internationally and domestically, and the USDP’s

determination to come out on top by hook or by crook, he looks likely to

stay in power until the end of the decade.

However, if Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and the president shift away from

the “making friends strategy,” Myanmar’s traditionally uncertain

political landscape could become even more unpredictable.

This story first appeared in the December 2012 print issue of The Irrawaddy magazine.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

WUNPAWNG MUNGDAN SHANGLAWT HPUNG A NINGGAWN MUNGMASA

WUNPAWNG MUNGDAN SHANGLAWT HPUNG A NINGGAWN MUNGMASA

CHYE JU KABA SAI

Sa Du N'Gun Jaw La ai Majaw N'chying wa Chyeju Dum Ga ai,Yawng a Ntsa Wa Karai Kasang Kaw na N'Htum N'Wai ai Shaman Chye ju Tut e Hkam La Lu Nga mu Ga law

No comments:

Post a Comment