By KO KO THETT

Since the 1922 introduction of a “legislative council” election to Burma, the notion of elections has always been suspect to the Burmese populace. This is not surprising, for Burma’s ballot boxes have never served their purpose—the electing of people’s representatives whose constitutional mandate can change or enforce government’s policy. Under both the British colonial administration and subsequent post-colonial governments, Burma’s elections have never translated into genuine political change.

In the 1920s, the dyarchy in which 80 members of the 130-member legislative council were elected and the rest were appointed by the British fractured the Burmese nationalist movement.

While moderates sought to change the system from within, radical nationalists in the movement called for “home rule”—a separation from British India—before they articulated independence for the country. The dyarchy election law disenfranchised most people in the peasantry since the suffrage for 44 constituencies in rural areas was based on the payment of taxation.

Out of a Burmese population of 12 million in 1922, there were only 1.8 million eligible voters. The voter turnout was very low, only 6.9 percent of eligible voters participated in Burma’s very first election.

The legislative council hopefuls were labeled “sellouts” to the British. Intimidation of the would-be voters by elections boycotters, nationalist monks and agitators was not uncommon. In fact, little effort was really needed to dissuade people, who had never known an election, from voting.

The second legislative council election in 1925 saw a 10 percent increase in voter turnout: 16.26 percent of the qualified voting population. The increased political participation was explained by the elected representatives’ success in making amendments to controversial laws, such as the 1907 Village Act of Burma and the 1920 Rangoon University Act. The attempts to encourage people into political participation by the elected politicians and the increased number of political parties also contributed to the increased voter turnout.

In 1927, the Simon Commission, chaired by Sir John Simon who was appointed by Westminster, started probing the possibility of “self-governing institutions” in Burma. British colonialists thought it expedient to keep Burma away from “the disturbing influence of Indian politics.” The 1930 Simon Commission report recommended that Burma be governed separately from India.

It took five years for the British to come up with the Government of Burma Act to implement the recommendations of the 1930 Simon Report. The constitution of 1935 discarded the dyarchy and added 33 new constituencies, increasing the number of ethnic Karen constituencies from five to 12.

By the time the 1936 election was held, all features of multi-party politics, from factionalism and forming coalitions to switching allegiance, flip-flopping, politicking, character assassination, party thuggery and boycotting of the electoral process were no longer new to the Burmese. The populace, by and large, learned to despise their politicians as much as they hated the British colonialists. The year also saw the Rangoon University strike and the emergence of the student activists Aung San and future premier Ko Nu as leaders of the hugely popular nationalist “Dobama Thakin” (“We Burmese Masters”) movement.

The thakin were not keen on “legislative politics” and downright rejected the 1935 Constitution. Yet the 1936 election on the offer was seen as a political opening by some dobama leaders. In the end the thakin belatedly founded the Komin-Kochin Aphwe (Our King, Our Affair Party) and fielded no less than 30 candidates to contest in the election. Ironically, one of their avowed aims was to disrupt the legislture's proceedings. Only three thakin were elected to the constituent assembly in 1936.

Fabian Ba Khine, one of the witnesses at the time, noted that the three elected thakin attended the assembly meetings with their adopted aim to revoke the 1935 Constitution and always sided with the party in opposition. They consistently opposed the government. It also meant that the thakin could not take up ministerial posts.

Senior politician Dr. Ba Maw, the founder leader of Sinyetha (Proletariat Party), became the first premier of Burma under the 1935 Constitution as he cleverly maneuvered different political forces to form a coalition government. Having formed her own government, Burma was finally separated from British India in 1937.

In the latter half of the 1930s, the ascendancy of Marxist politics in the Dobama movement naturally led to the consideration of “independence by any means” and extra-parliamentary activities to overthrow the British.

Jun 1, 2010

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

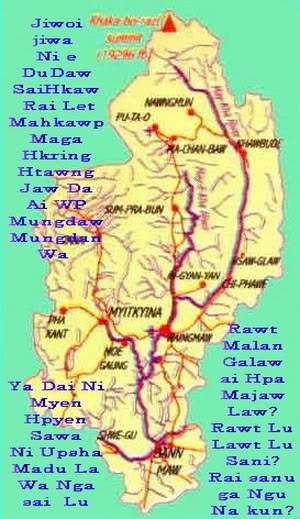

WUNPAWNG MUNGDAN SHANGLAWT HPUNG A NINGGAWN MUNGMASA

WUNPAWNG MUNGDAN SHANGLAWT HPUNG A NINGGAWN MUNGMASA

CHYE JU KABA SAI

Sa Du N'Gun Jaw La ai Majaw N'chying wa Chyeju Dum Ga ai,Yawng a Ntsa Wa Karai Kasang Kaw na N'Htum N'Wai ai Shaman Chye ju Tut e Hkam La Lu Nga mu Ga law

No comments:

Post a Comment