Special Warfare, Dec, 2002 by C.H. Dr. Briscoe

Early in 1942, the outlook for the Allies was grim in the China-Burma-India theater, or CBI. The Japanese navy had driven the British navy from the Java Sea, Singapore had fallen in February; and the Japanese were simultaneously attacking the Dutch East Indies (to seize the oil refineries and rubber plantations) and Burma (to block the British land connection to China).

Because the Burma Road was the only Allied land bridge to China, General Chiang Kai-shek had sent the Chinese Expeditionary Force to Burma in mid-January 1942 to help Great Britain stop the Japanese offensive there. United States Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson chose Lieutenant General Joseph W. Stilwell to head U.S. forces in the OBI theater and to keep the Chinese fighting.

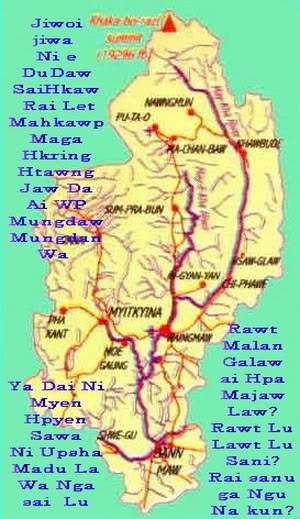

However, by the time Stilwell arrived in Burma in March 1942, the Japanese had already captured Rangoon and were advancing north along the railway toward Mandalay and Myitkyina. An unexpected Japanese flank attack out of Thailand crushed the 1st Burmese Division at Yenangyuang and permitted the Japanese to concentrate their forces. They destroyed the 55th Chinese Division at Loilemis and blocked any attempts by Allied forces to escape to China via the Burma Road.

Having only two options--walking out of Burma and into India, or becoming a prisoner of war--the newly-arrived American commander concentrated on saving his U.S. military staff and a group of American, British, Chinese, and Indian civilians and Burmese nurses--about 100 people. The 60-year-old Stilwell spent the first 19 days of May 1942 leading his entourage some 200 miles from Wuntho to Imphal, India, following dirt roads, rafting rivers, and climbing the forest trails across the eastern razorback mountains of India.

Although Stilwell escaped the Japanese, the critical Burma link in the Allied theater had been lost. India was Great Britain's last bastion in Asia. Ramgarh in India's Bihar province became the major training ground for Allied forces in the CBI theater. Anxious to get back into the fight, but facing a demoralized British army and the awesome task of building another Chinese force, Stilwell prepared for the future by building a supply road to Ledo to support an invasion of Burma.

Newly formed Chinese infantry divisions were flown across "the Hump" to be trained at Ramgarh by an American cadre for service with the British 14th Army. The British provided barracks, food and silver rupees to pay the Chinese troops, while the Americans furnished radios, rifles and machine guns, artillery, tanks, trucks and instructors. In addition to teaching infantry, tank, and artillery tactics, the American soldiers changed truck tires and loaded pack mules.

During the Chinese train-up and the British reconstitution of forces, bill tribes in northern Burma who refused to be subjugated -- predominantly the Kachins, but also the Karens, the Chins, the Kukis and the Nagas -- had been fighting a guerrilla war against the Japanese occupation forces. Other Burmese tribes, the Burmese and the Shans, welcomed the Japanese and openly collaborated with the Japanese secret police (Kempei) against the minority hifl tribes. The Allies supported the guerrillas from Fort Hertz, the only remaining Allied base in Burma that had an airfield. The three regiments of guerrillas -- the Karen Rifles, the Kachin Rifles, and the Kachin Levies -- were natural jungle fighting units, but they lacked the tactical training and the modern equipment that were needed to effectively battle Japan's mechanized infantry and armor.

It took Major General Orde Wingate to show that the Japanese army could be beaten and to rekindle an offensive spirit among the Allies in India. Wingate had led a force of 80 British soldiers and 1,000 Ethiopians and Sudanese across 600 miles of desert to restore Emperor Haile Selassie to his throne in Addis Ababa in 1941. In April 1942, Wingate arrived in India to organize guerrilla levies against the Japanese in Burma. But rather than use the Kachin resistance, Wingate chose to lead a long-range penetration group, composed of British regulars and colonial units, behind Japanese lines to exploit the vulnerabilities of the occupation force with unconventional warfare.

Wingate's force, the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade, the "Chindits," was formed from the 13th Battalion, King's Liverpool Regiment; the 3rd Battalion, 2nd Ghurka Rifles; the 2nd Battalion, Burma Rifles; and the 142nd Commando. After extensive training at Ramgarh, the 3,000 Chindits moved more than 200 miles behind Japanese lines in Burma. Relying solely on air assets for resupply and medical evacuation, the Chindits ambushed Japanese patrols, attacked outposts and supply depots, destroyed bridges and repeatedly cut the Myitkyina railroad for more than three months. Afterward, they dispersed into small groups that either returned to India or escaped to China.

Fewer than half the raiders returned -- malnutrition, combat fatigue, disease, death and wounds had thinned their ranks. Lieutenant General William J. Slim, commander of the British 14th Army, criticized Wingate's effort as an expensive failure, but Winston Churchill praised Wingate's genius and brought him to the Quebec Conference in August of 1943. There, Wingate proposed a second, larger Chindit expedition and suggested that the U.S. Office of Strategic Services, or OSS, expand its guerrilla-warfare activities into Burma.

The existing resistance of the Kachins and other hill tribes dovetailed perfectly with the British plan to support small units operating behind Japanese lines (the plan was called "Guerrilla Forces--Plan V"). In August 1943, a British V-Force team flew to Fort Hertz to reconstitute the Kachin Levies. Stilwell also diverted to Fort Hertz eight officers and 40 sergeants (radiomen, cryptographers and medics) from the American soldiers who had been assigned to train the Chinese infantry divisions. From that remote outpost, they were to expand the partisan war in Burma by advising and supporting the Kachins in conducting guerrilla warfare behind Japanese lines.

The V-Force recruited the hill tribesmen and trained them to collect intelligence; to provide early warnings of air attacks; to recover downed Allied aircrews; to conduct ambushes, reconnaissance and flank patrols; and to scout for conventional forces. To complement their experience as infantrymen, the V-Force advisers had acquired skills in language, medicine, demolition, radio and cryptology. They transmitted coded messages to relay their daily intelligence reports and to request air resupply and medical evacuation. British units operated from Ledo north to Fort Hertz, from Kohima to Chindwin, and in the mountains west of Imphal. American teams worked south to Myitkyina, sending their reports to Ledo and to Tagap-Ga, their forward logistics base.

The successes of the V-Force Kachin Rangers and the Kachin Levies, as well as Stilwell's failure to garner support from the Chinese and from the British army for a conventional offensive against Burma, led Stilwell to expand his guerrilla operations. He directed OSS Detachment 101 to establish its headquarters m Assam, in northeastern India. Det 101's assignment was to plan and conduct operations against the roads and the railroad into Myitkyina, in order to deny the Japanese the use of the Myitkyina airfield. Det 101 would coordinate its operations directly with the British. Det 101's Lieutenant Colonel Carl Eifler was given a free hand in directing sabotage and guerrilla operations. All Stilwell wanted to hear was "booms from the Burmese jungle." By November 1943, at his base in the Naga Hills of northern Assam, Eifler was preparing the first group of Allied agents for Burma.

By the end of 1943, Det 101 had established six Kachin operating bases behind the lines in northern Burma: three east of the Irrawaddy River and three west of it. Each base commander recruited and trained small Kachin elements for his personal protection, for internal defense, and for conducting limited operations--principally sabotage and small ambushes. The guerrilla forces were uniformed and equipped with air-supplied M-2 .30-cal. carbines, submachine guns (.45-cal. Thompson and 9 mm Marlin), .30-cal. light machine guns, ammunition and demolitions. Japanese arms and equipment in northern Burma were a decade behind the times, and the superior firepower of the guerrilla units was key to their success. Each Kachin camp had an intelligence officer, usually an American officer, whose principal duties were to interrogate captured enemy soldiers or agents, debrief guerrilla patrols, and direct operations of the better-educated Kachins (those schooled by Christian missionaries), who acted as low-level intelligence agents reporting information by runners or via bamboo-container message drops.

Det 101 recruited potential agents from the Kachin and Karen guerrillas. The candidates slipped through Japanese lines to reach the airfield at Fort Hertz, from which they were flown to Assam for three to five months of intensive intelligence and communications training. The Kachins proved to be particularly adept at continuous-wave radio communications--most were able to send and receive 25-45 words per minute. While most returned to their former bases, a few parachuted into new areas to organize independent operations and to collect and report weather data to the 10th AF Weather Service. This data was critical to air resupply and daily "over the Hump" C-46 and C-47 transport missions to China.

Despite reports of successful guerrilla operations and the volume of intelligence coming from the field, Stilwell remained skeptical about Det 101's effectiveness until Det 101's Major Ray Peers flew two Kachin leaders to Stilwell's headquarters. When the Kachins told Stilwell how many Japanese they had killed in various ambushes and raids, he asked for proof, thinking that 200 miles behind enemy lines, they could have spent little time counting Japanese dead and wounded. The two Kachin leaders were unperturbed. They unhooked bamboo tubes from their belts and dumped the contents of the tubes on Stilwell's field desk. When asked what the contents were, the Kachins replied: "Japanese ears. Divide by two and that is how many we have killed." In the Burmese hill tribes, ears taken in combat denoted a warrior's courage. It was sufficient proof for Stilwell. But after the Kachins departed, Peers received a lecture on the Rules of Land Warfare. It took months to convince the Kachins that body counts would suffice.

Stilwell's opinion of special operations rose. He had to admire Det 101 and the Kachins, because unlike the British and Chinese forces, they were fighting the Japanese and providing valuable intelligence. In the late summer of 1943, Stilwell approved plans for the fall-winter offensive of 1943-44, a three-pronged drive into Burma.

Stilwell would launch the first prong, the north Burma campaign, in late December, in an attempt to seize the airfield and the rail terminus at Myitkyina before the spring monsoons. Success would seal the winter campaign with a victory; put Stilwell halfway to China, and break the Japanese blockade. Stilwell would lead the 22nd and 38th Chinese Divisions,two of the three Chinese divisions training at Ramgarh. The Chinese divisions would be supported by Merrill's Marauders and the British and American Kachin elements. By abandoning fixed supply lines and making his force dependent on air resupply, Stilwell hoped to eliminate the possibility of retreat by the untested Chinese troops. Stilwell planned to push the force 200 miles through jungle, through swamp and over mountains to conquer an entrenched, desperate enemy. Fearing that the Chinese might falter without an American vanguard, Stilwell put Merrill's Marauders in the lead.

The second prong would be a second division-sized Chindit expedition led by Wingate in central Burma, far to the south of Stilwell's force. The Chindits, with the support of the 1st Air Commando, led by Colonels Philip Cochran and Robert Allison, were to launch a glider-borne assault into three landing zones. The third prong would consist of a drive by the 14th British Army into central Burma behind the Chindits.

On the map, the Allied campaign for northern Burma wriggled tortuously from one unpronounceable name to another, but on the ground, the soldiers faced rain, heat, mud, sickness, snakes, snipers and ambushes. In February, the Marauders wheeled about on the eastern flank of the main Chinese advance, moving through the jungle to attack each Japanese defensive position from the rear. The Kachin Levies at Fort Hertz guarded the rear of the advance as Stilwell's main force descended southward. Some 3,000 Kachin Rangers of Det 101 assisted the Marauder battalions.

Lieutenant James L. Tilly's detachment of Kachin Rangers scouted for the 1st Marauder Battalion and provided its flank guard. Captain Vincent Curl's 300 Kachin Rangers scouted for the 2nd and 3rd Marauder battalions, guarded their eastern flanks, ambushed Japanese patrols and destroyed retreating Japanese forces. During the march, the Kachin Rangers also rescued two downed pilots from the 1st Air Commando.

The presence of native jungle fighters instilled confidence among the Marauders. Lieutenant Charlton Ogburn Jr. declared, "Often we had a Kachin patrol with us, and we never, if possible, moved without Kachin guides. The Kachin Rangers not only knew the country and the trails, but they also knew better than anyone, except the enemy, where the Japanese outposts were located. Waylaying Japanese in their artful ambushes, they made us think of a Robin Hood version of the Boy Scouts, clad (when in uniform) in green shirts and shorts. Some of the warriors could not have been more than 12 years old. While most carried the highly lethal burp guns (Thompson and Marlin submachine guns) slung around their necks, some carried ancient muzzle-loading, fowling pieces." All the Kachins also carried their traditional machete-like short swords, called dahs.

In April, when his Chinese division commanders stalled (blaming their failure to destroy the Japanese 18th Division on bad weather and combat delays), Stilwell took a desperate risk. On April 21, keeping the two Chinese divisions directed toward the Mogaung Valley to assault Kamaing, Stilwell launched a separate strike force of 1,400 Americans, 4,000 Chinese, and 600 Kachins across the Kumon mountains to seize the Myitkyina airstrip in a lightning push.

On April 25, the 5307th split into three assault columns: the 1st Marauder Battalion with Kachin Rangers leading the Chinese 150th Infantry Regiment; the 3rd Marauder Battalion with Kachin Rangers leading the Chinese 88th Infantry Regiment; and a smaller third force, composed of the 2nd Marauder Battalion (which was at 50-percent strength), 300 Kachin Rangers, and a battery of 75 mm pack howitzers. The force was to preserve radio silence until it was within a 48-hour march of Myitkyina. Then, it was to radio a code word to alert the 10th USAAF to fly reinforcements into the secure airstrip.

The Kachins believed that the steep Kumon mountain range could not be crossed by pack animals in wet weather, but Stilwell was determined that the strike force would try. At Arang, one of the Kachin guides suggested that they follow an old, unused track over the mountains. Greased with mud, the trail proved all but impassable. The soldiers of the Myitkyina strike force pulled clambering mules and, at times, crawled upward on their hands and knees, covering only 4-5 miles a day.

The force lost half its pack animals. With each lost mule went 200 pounds of supplies. Colonel Henry L. Kinnison Jr., commander of the 3rd Marauder Battalion, and several of his men died of mite typhus. When the 2nd and 3rd battalions stopped to wait for rations, Colonel Charles N. Hunter's 1st Battalion team forged ahead, with the Kachins leading. When the only scout who knew the trail was bitten by a poisonous viper, the medics applied a tourniquet close to the bite and sucked most of the poison from the wound. Strapped aboard Hunter's horse, the Kachin managed to guide the Marauder task force behind the Japanese lines undetected.

On May 14, Hunter sent the 48-hour alert code to Stilwell. The Kachin scouts had slipped into Myitkyina, discovered no evidence that the Japanese were on increased alert, and reported that the airstrip was lightly guarded. The 1st Marauder Battalion attacked the ferry terminal on the Irawaddy River as the 150th Chinese Regiment seized the airfield to open the way for air-landed reinforcements. General Lord Mountbatten attributed the undetected crossing of the Kumon mountain range to Stilwell's bold leadership; he attributed the capture of the Myitkyina airstrip to the courage and endurance of the American, Chinese and Kachin troops.

The next day, however, the Chinese made a double envelopment of Myitkyina that turned into a debacle. During the attack, the two Chinese regiments inflicted such heavy casualties on each other that they had to be withdrawn. The setback gave the Japanese time to reinforce the town's defenses. As the monsoons descended in earnest on northern Burma (bringing 175 inches of rain), the lightly-held airfield was hit by heavy Japanese counterattacks and artillery barrages almost daily. The battle for the town of Myitkyina dragged on, consuming June and July before it finally ended in early August 1944.

By then, Det 101 had shifted most of its elements 100 miles south. There Det 101 was directing more than 100 intelligence operations and had more than 350 agents in the field. As the 14th British Army began its drive into central Burma (the third prong of the attack), Det 101 units were attacking Japanese lines of communication as far south as Toungoo.

However, between the Myitkyina-Mandalay-Rangoon railway and the 14th British Army lay a 250-mile gap that contained a series of parallel north-south corridors. Those corridors provided natural approaches to the Ledo Road. The Kachin Rangers protected the gap, fending off several major Japanese probes there. Orders called for the Kachin Rangers to withdraw and inactivate once the 14th British Army had captured Lashio and Mandalay, but heavy fighting in southern China ended those plans. The bulk of the Chinese and American forces in Burma were flown to China.

Lieutenant General Dan Sultan, Stilwell's successor, directed Detachment 101 to use the Kachin Rangers to mop up the southern Shan States and to seize the Taunggyi-Kengtung road, a Japanese escape route to Thailand. The Kachins were tired and a long way from home, but 1,500 of them volunteered for the mission; the remainder were given transportation home. Using the Kachin Rangers as a nucleus, Det 101 organized a 3,000-man guerrilla force of Kachin, Karen, Ghurka, Shan, Chinese, and Burmese forces into four line battalions.

The Japanese were not ready to be "mopped-up" by four battalions of guerrillas who were trying to fight conventionally behind the lines. As a result, some of the bloodiest fighting for the Kachins took place during those final months. Although the Det 101 guerrillas killed more than 1,200 Japanese, they suffered more casualties (including 300 killed in action) during those final months than during any other period in the war.

Before the mission in the Shan States, some of the Kachin Rangers had already been reassigned to support the newest long-range penetration force, the 5332nd Provisional Brigade, known as the Mars Task Force. When Merrill's Marauders were deactivated Aug. 10, 1944, seven days after the capture of Myitkyina, the Mars Task Force, commanded by Brigadier General John P. Miley, assumed its mission for long-range penetration operations in Burma. The Kachin Rangers fought with the task force at Bhamo and Lashio, the terminus of the Burma Road.

Before OSS Detachment 101 was inactivated July 12, 1945, Lieutenant Colonel Ray Peers conducted a formal "mustering out" of the Kachin Rangers during their victory celebration in Simlumkaba. Blueribboned CMA medals (Citation for Military Assistance) and silver bars with Det 101's lightning logo and "Burma Campaign" engraved on them were presented to all Kachin Rangers. Those Kachins who had "endured the cruelest tests of battle" were awarded captured Japanese samurai swords and sniper rifles.

An excerpt from Detachment 101's Presidential Unit Citation, awarded for the unit's capture of strategic Japanese strong points of Lawsawk, Pangtara and Loilem in Burma's Central Shan States from May 8 to June 15, 1945, characterizes the warrior ethos of the Kachin Rangers: "American officers and men recruited, organized, and trained 3,200 Burmese natives entirely within enemy territory. They successfully conducted a coordinated four-battalion offensive against important strategic objectives defended by more than 10,000 battle-seasoned Japanese troops. Locally known as 'Kachin Rangers,' Detachment 101 and its Kachin troops became a ruthless striking force, continually on the offensive against the veteran Japanese 18th and 56th divisions. Throughout the offensive, Kachin Rangers were equipped with nothing heavier than mortars. They relied only on air-dropped supplies and by alternating frontal attacks with guerrilla tactics, the Kachin Rangers maintained constant contact with the enemy and persistently cut hi m down and demoralized him."

Although they were cited officially only by the Americans, the Kachins were heavily involved in the heterogenous China-Burma-India theater. They fought as levies with the British from Fort Hertz; supported Wingate's two Chindit expeditions; fought, collected intelligence, reported weather and rescued downed Allied aircrews for OSS Detachment 101; fought with Merrill's Marauders and the Chinese, and fought with the Mars Task Force.

Recent Army special-operations lessons learned from Afghanistan reveal some commonalities with lessons learned by the Kachin Rangers:

* The relationships established by ethnic Kachins with missionaries and with British officials in the colonial administration were similar to those built by government agencies with exiled minority group leaders in Afghanistan.

* Air resupply, critical for equipping and resupplying guerrilla forces in enemy territory in the mid-1940s, was equally important in Afghanistan in 2002.

* Technical training of indigenous troops continues to be extremely difficult in areas in which illiteracy is high. Almost all Kachin and Karen radio operators who achieved a send-and-receive rate of 25-45 words per minute in 1943 had received some education from missionaries.

* Advising and training guerrilla forces continues to be a valuable mission. Indigenous peoples are the best sources of local intelligence and information; and if properly trained, they can assist with the rescue of downed aviators.

* In 1943, language was as much an obstacle to communicating with and training indigenous groups as it is today.

* Respect of culture, customs and social structure were as critical in Burma during World War II as they are in Afghanistan today.

* The Western world's Law of Land Warfare continues to be difficult to explain to partisans from other cultures.

* Guerrilla elements operate best in areas with which they are most familiar; Kachins tasked to fight Japanese in the southern Shan States faced the same problems that Allied conventional forces encountered-- uncooperative and suspicious locals, a lack of familiarity with the terrain, traditional ethnic hostility between groups, different languages and different customs.

* Ethnic-group boundaries, while not marked on maps, are recognized by the different groups, whether in Afghanistan today or in Burma in 1944.

* The American cause is not necessarily the guerrilla cause, nor is it the reason that ethnic groups band together against a common enemy.

* Finally, an OSS Washington staff officer reported that the Kachin Rangers were the "most trigger happy group of armed men I have ever seen, [but] we still kept them loaded down with all the extra ammunition we could find because they were fighting."

Sources:

British Air Ministry Wings of the Phoenix: The Official Story of the Air War in Burma (London: His Majesty's Stationery Office, 1949).

Dunlop, Richard. Behind Japanese Lines: With the OSS in Burma (New York: Rand McNally, 1972).

Fletcher, James A. "Kachin Rangers: Fighting with Burma's Guerrilla Warriors," in Special Warfare (July 1988), Secret War in Burma (Atlanta: 1997), and interview by Dr. C.H. Briscoe, Austell, Ga., 18 September 2002.

Hilsman, Roger. American Guerrilla: My War Behind Japanese Lines (New York: Brasseys, 1990).

Hogan, David W. Jr. "MacArthur, Stilwell, and Special Operations in the War Against Japan," in Parameters (Spring 1995).

Ogburn, Chariton Jr. The Marauders (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1956).

Peers, William R. "Guerrilla Operations in Northern Burma," in Military Review (June 1948), "Intelligence Operations of OSS Detachment 101," in Studies in Intelligence 4:3 (1960) reprinted in a special OSS 60th Anniversary Edition (June 2002); Peers and Dean Brelis. Behind the Burma Road: The Story of America's Most Successful Guerrilla Force (Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1963), and Peers, "Guerrilla Operations in Burma," in Military Review (October 1964).

Romanus, Charles F., and Riley Suaderland. United States Army in World War II: China-Burma-India Theater: Time Runs Out in CBI. Washington, D.C.: Office of the Chief of Military History, U.S. Army, 1959.

Smith, R. Harris. OSS: The Secret History of America's First Central Intelligence Agency (Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press, 1972).

Stilwell, Joseph W., and Theodore W. White. The Stilwell Papers (New York: Schocken Books, 1972).

Taylor, Thomas. Born of War (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1988).

Tuchman, Barbara W. Stilwell and the American Experience in China, 1911-45 (New York: Macmillan, 1971).

U.S. War Department. Assistant Chief of Staff, G-2, Army Ground Forces. Report of Combat Experiences with OSS (25 September 1943), by Lieutenant Colonel Jack R. Shannon.

Dr. C.H. Briscoe is the command historian for the US. Army Special Operations Command.

COPYRIGHT 2002 John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group

Oct 30, 2009

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

WUNPAWNG MUNGDAN SHANGLAWT HPUNG A NINGGAWN MUNGMASA

WUNPAWNG MUNGDAN SHANGLAWT HPUNG A NINGGAWN MUNGMASA

CHYE JU KABA SAI

Sa Du N'Gun Jaw La ai Majaw N'chying wa Chyeju Dum Ga ai,Yawng a Ntsa Wa Karai Kasang Kaw na N'Htum N'Wai ai Shaman Chye ju Tut e Hkam La Lu Nga mu Ga law

No comments:

Post a Comment