By GAYATRI LAKSHMIBAI

It’s a cloudy, grey Friday afternoon in the Mae La Oo refugee camp on the Thai-Burma border. Hla Htay, the headmaster of the Yaung Ni Oo school, sits in his bamboo hut with a keen eye on proceedings at the school just across the narrow mud lane. He takes a puff out of his cigarette. “These are Burmese cigarettes, they are good. Would you like to try one?” he asks with a palpable sense of pride.

It’s uncharacteristic of Hla Htay to be home on a weekday. He explains why he isn’t teaching his tenth standard students lessons in English grammar and History today – he’s been unwell with fever and hypertension over the last couple of days.

A former All Burma Students’ Democratic Front (ABSDF) soldier, Hla Htay has been head of the ABSDF-run school since 1998. He joined the student armed rebellion group during its inception around the 1988 uprising in Rangoon.

Having been in the conflict zone fighting the Burmese military for five years since 1992, Hla Htay is now content with having put his guns to rest. “I do miss being on the frontline sometimes, but I know teaching young children is going to have a bigger impact,” he says.

The school has 540 students and 24 teachers. Once a hardline ABSDF-governed entity, the group’s ideological hold over the school seems to be waning. While some years ago, all staff members were essentially ABSDF members, today only four out of 24 teachers at the school represent the organisation.

“The younger teachers these days don’t want to be politically inclined. I get a feeling that they are just here, waiting hopefully to have a better life, maybe in a third country. Given a choice, most of them wouldn’t want to go back to Burma,” Hla Htay says with disappointment.

Resettlement programmes for Burmese refugees in third countries like the US, Australia, a few nations in the EU and Japan are alluring the young bunch of teachers at Yaung Ni Oo. With opportunities for further education, secure jobs and a better standard of living, returning to Burma to continue the struggle previous generations have waged seems like fighting a losing battle.

Shar Gay Mu, a 23-year-old Karen woman, who passed tenth standard at the school is now a science teacher for the third and fourth grade students. She began teaching a year ago, after having successfully finished a teacher-training programme. However, Shar Gay Mu has no long-term plans to continue working there.

“I have applied for resettlement. It’s been three years, a long wait,” she says. The resettlement procedures overseen by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) are a long drawn bureaucratic process made more complicated by the increasing number of refugees seeking asylum in camps on the Thai-Burma border.

Shar Gay Mu wants to pursue further education and she is aware that she wouldn’t be able to pursue her goals inside Burma or in the refugee camp. “I wanted to be a doctor when I was younger, but I realised soon enough that it will always remain a dream. Becoming a teacher seemed plausible, so I took it up. I want to go outside now and study more. That will help me become a better teacher,” she says with conviction.

When you ask her what she thinks of the ABSDF, she shrugs. “I really don’t care about politics in Burma. I don’t want to be part of any group. The best I can do is be a good teacher — that’s my job and I care only about it.”

Another 25-year-old maths teacher for ninth and tenth grade at Yaung Ni Oo, Sunday, echoes Shar Gay Mu’s thoughts. A ‘new arrival’ at the camp, Sunday is getting used to life inside Mae La Oo after having spent many years inside Burma.

He has now set goals for himself and Burma doesn’t feature in his scheme of plans. “I don’t want to ever go back to Burma,” he says, “Things will never change there.” Instead, he finds meaning in wanting to pursue studying English in Australia. “It’s more useful for me to learn the language. I want to survive in the outside world and English will help.”

Hla Htay is well-versed with the ground reality and disheartened by them, to say the least. “Ten years ago if I asked students who would want to fight the military with me, all of them would raise hands. It’s not the same any more. Children want a good future for themselves,” he says. Students at the school have varying ambitions; they want to be medics, doctors, automobile mechanics or teachers.

“It’s unfair to expect everyone to sacrifice their lives for Burma. They have seen their parents do it [fight against the military], and that is a good enough example for them to stay away. They see it as an endless struggle, I don’t blame them,” Hla Htay concedes.

He can empathise with the youngsters’ decision to stay away from the armed struggle led by the ABSDF, “The violent struggle is losing its sheen with each passing day. There’s increasingly no difference in the kind of irregularities rebel armies and the SPDC commit – that is a reason which has led to disillusionment among the new generation.”

While a large proportion of youngsters wish to be resettled in a developed country never to return to Burma, there is still a small percentage that wants to carry forward the democratic struggle. Last year, the school produced seven students who are currently serving rebel armies in the jungles of Burma.

Losing track of its strong ideological leaning is, according to Hla Htay, only one of the serious problems facing Yaung Ni Oo. Funding is another. The school is the only one in the predominantly Karen populated refugee camp that follows Burmese instead of Karen curriculum. The reason: the school believes more in the unification of Burma than supporting the cause of an ethnic group.

One of the biggest funding bodies in the education sector, ZOA Refugee Care, has a diktat of funding schools that follow the Karen curriculum. The school’s stubbornness in this regard has ruled out obtaining funds from ZOA. Affiliation to ABSDF, which is an armed struggle group, is another justification for international NGOs to cut ties with the school.

Yaung Ni Oo currently has no NGO-support. “All the funding comes from personal donations by former ABSDF members. It’s becoming more and more difficult to keep the school running. We need 50,000 Thai baht per month for all operations – it’s a lot of money to be raised just by way of donations,” Hla Htay says.

With the Thai government announcing recently that all refugees will be expected to return to Burma after the upcoming elections, the future of the school could take another uncertain turn. In a year’s time, the school might well cease to exist and all the time and effort invested over the past two decades could meet a sudden end.

Such ambiguities put Hla Htay, who has a two-year-old son Aung Doo, in a serious dilemma. While he surely wants his son to have a secure and prosperous future, he can’t imagine “turning his back” on Burma. “I have told my wife that she and Aung Doo should apply for resettlement, but they don’t want to leave without me. I, on the other hand, am weighed down by responsibility,” he says.

The school headmaster is one of the 15,000 inhabitants at Mae La Oo treading a path between being hopeful, disillusioned and hopeless. With each passing day, they see their life slip by waiting relentlessly for something positive to unfold.

Sep 17, 2010

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

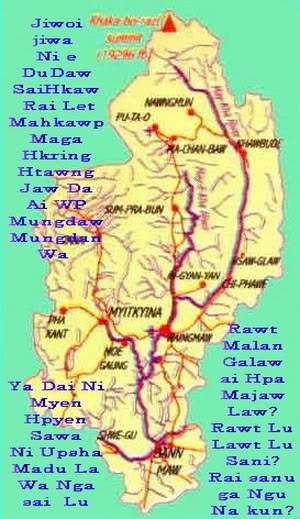

WUNPAWNG MUNGDAN SHANGLAWT HPUNG A NINGGAWN MUNGMASA

WUNPAWNG MUNGDAN SHANGLAWT HPUNG A NINGGAWN MUNGMASA

CHYE JU KABA SAI

Sa Du N'Gun Jaw La ai Majaw N'chying wa Chyeju Dum Ga ai,Yawng a Ntsa Wa Karai Kasang Kaw na N'Htum N'Wai ai Shaman Chye ju Tut e Hkam La Lu Nga mu Ga law

No comments:

Post a Comment