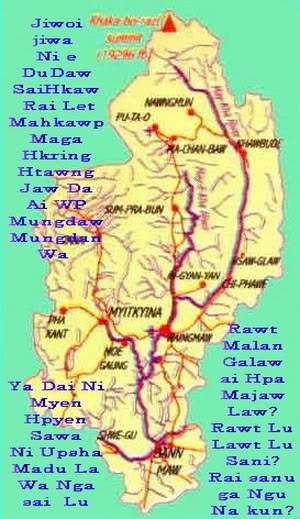

The Burmese junta decribed the Kachin Independence Army (KIA), a cease-fire group which operates on the Sino-Burmese border, as “insurgents” in state-run-newspapers on Friday, ceasing to call them a cease-fire group which they have done since signing a cease-fire agreement with the KIA in 1994.

The state-run newspapers described the KIA as “insurgents” in a report blaming the KIA for a mine blast which killed two and injured one in Kachin State on Wednesday.

The report came amid Naypyidaw’s flaring tensions with the cease-fire ethnic groups including the KIA over the Border Guard Force (BGF) plan, which ordered the groups to transform their independent militia's into a Burmese army-controlled BGF.

Five villagers from Mogaung Township, Kachin State “stepped on a mine planted by KIA insurgents” in “Kachin Special Region-2”, the state-run-newspaper The New Light of Myanmar said.

Responding to Naypyidaw’s usage of “insurgents,” Wawhkyung Sinwa, a spokesman for the Kachin Independence Organization (KIO), the political wing of the KIA, told The Irrawaddy on Friday that it is incorrect to describe a cease-fire group as insurgents while the cease-fire remains in operation.

He added that although the ceasefire has not yet broken down into armed conflict, tension between the regime and the KIA is high. “The situation is more or less normal for us,” he said, referring to the high state of tension.

Observers in Rangoon who read the newspapers were surprised by the junta’s tone toward the KIA.

“After reading the report, I was shocked because insurgent is a term the regime has only used for non-ceasefire groups such as the Karen National Union in the last 20 years,” said an editor of a private Rangoon weekly speaking on condition of anonymity. “It also signals a potential new civil war in the country's border areas.”

Military sources in Rangoon said they learned some light infantry battalions normally stationed around Rangoon were ordered to deploy in Kachin State this week. The junta also recently purchased 50 Mi-24 military helicopters from Russia for counter insurgency operations, said observers.

In late September, KIA soldiers shot at a Burmese military helicopter that flew over the KIO headquarters at Laiza, which was considered unusual since the cease-fire agreement normally deterred such acts on both sides.

After a major military reshuffle in junta forces in late August, the two main junta commanders dealing with the KIA, Lt-Gen Tha Aye, chief of Bureau of Special Operation (BSO)-1 and Maj-Gen Soe Win, commander of the Northern Regional Military Command were replaced by Maj-Gen Myint Soe of the Northwest Regional Military Command and Brig-Gen Zayar Aung, commandant of the Defense Services Academy.

The new replacement commanders have yet to hold any meetings with the KIO since taking up their appointments, said KIA sources in Laiza.

“New commanders usually come to introduce themselves and create cordial relations, but we haven't seen either Maj-Gen Myint Soe or Brig-Gen Zayar Aung,” a KIO official said.

When the junta, then called the State Law and Order Restoration Council, and the KIO officially announced the cease-fire agreement, the agreement was based on three topics—peace under a cease-fire in Kachin State and related areas in northern Shan State, economic development in the area and a commitment to work for peace across Union of Burma.

The KIA and its allies on the Sino-Burmese border such as the United Wa State Army and the National Democratic Alliance Army (NDAA—also known as the Mongla group) rejected the junta’s BGF plan under the 2008 constitution saying it could not guarantee ethnic rights.

Meanwhile, the junta has suspended the November elections in the group’s areas due to ongoing tension in the area and the prospect of being unable to win, according to observers.

The BGF tension on the Sino-Burmese border became a regional stability issue when an estimated 37,000 Kokang-Chinese refugees fled from Burma to China after the junta launched a surprise offensive against the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA) in Kokang in August 2009.

Since then, Beijing has been worried about potential conflict in neighboring border areas in the post-election period.

“For a risk-averse Beijing, it all makes for a volatile mix in an election year. At a time when China is pushing border stability in Myanmar [Burma], elections lacking participation from major border ethnic groups—the Wa, Kachin and others—may set the stage for potential conflict,” said Stephanie Kleine-Ahlbrandt, the International Crisis Group’s North East Asia Project Director in Beijing in a recent article.

The state-run newspapers described the KIA as “insurgents” in a report blaming the KIA for a mine blast which killed two and injured one in Kachin State on Wednesday.

The report came amid Naypyidaw’s flaring tensions with the cease-fire ethnic groups including the KIA over the Border Guard Force (BGF) plan, which ordered the groups to transform their independent militia's into a Burmese army-controlled BGF.

Five villagers from Mogaung Township, Kachin State “stepped on a mine planted by KIA insurgents” in “Kachin Special Region-2”, the state-run-newspaper The New Light of Myanmar said.

Responding to Naypyidaw’s usage of “insurgents,” Wawhkyung Sinwa, a spokesman for the Kachin Independence Organization (KIO), the political wing of the KIA, told The Irrawaddy on Friday that it is incorrect to describe a cease-fire group as insurgents while the cease-fire remains in operation.

He added that although the ceasefire has not yet broken down into armed conflict, tension between the regime and the KIA is high. “The situation is more or less normal for us,” he said, referring to the high state of tension.

Observers in Rangoon who read the newspapers were surprised by the junta’s tone toward the KIA.

“After reading the report, I was shocked because insurgent is a term the regime has only used for non-ceasefire groups such as the Karen National Union in the last 20 years,” said an editor of a private Rangoon weekly speaking on condition of anonymity. “It also signals a potential new civil war in the country's border areas.”

Military sources in Rangoon said they learned some light infantry battalions normally stationed around Rangoon were ordered to deploy in Kachin State this week. The junta also recently purchased 50 Mi-24 military helicopters from Russia for counter insurgency operations, said observers.

In late September, KIA soldiers shot at a Burmese military helicopter that flew over the KIO headquarters at Laiza, which was considered unusual since the cease-fire agreement normally deterred such acts on both sides.

After a major military reshuffle in junta forces in late August, the two main junta commanders dealing with the KIA, Lt-Gen Tha Aye, chief of Bureau of Special Operation (BSO)-1 and Maj-Gen Soe Win, commander of the Northern Regional Military Command were replaced by Maj-Gen Myint Soe of the Northwest Regional Military Command and Brig-Gen Zayar Aung, commandant of the Defense Services Academy.

The new replacement commanders have yet to hold any meetings with the KIO since taking up their appointments, said KIA sources in Laiza.

“New commanders usually come to introduce themselves and create cordial relations, but we haven't seen either Maj-Gen Myint Soe or Brig-Gen Zayar Aung,” a KIO official said.

When the junta, then called the State Law and Order Restoration Council, and the KIO officially announced the cease-fire agreement, the agreement was based on three topics—peace under a cease-fire in Kachin State and related areas in northern Shan State, economic development in the area and a commitment to work for peace across Union of Burma.

The KIA and its allies on the Sino-Burmese border such as the United Wa State Army and the National Democratic Alliance Army (NDAA—also known as the Mongla group) rejected the junta’s BGF plan under the 2008 constitution saying it could not guarantee ethnic rights.

Meanwhile, the junta has suspended the November elections in the group’s areas due to ongoing tension in the area and the prospect of being unable to win, according to observers.

The BGF tension on the Sino-Burmese border became a regional stability issue when an estimated 37,000 Kokang-Chinese refugees fled from Burma to China after the junta launched a surprise offensive against the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA) in Kokang in August 2009.

Since then, Beijing has been worried about potential conflict in neighboring border areas in the post-election period.

“For a risk-averse Beijing, it all makes for a volatile mix in an election year. At a time when China is pushing border stability in Myanmar [Burma], elections lacking participation from major border ethnic groups—the Wa, Kachin and others—may set the stage for potential conflict,” said Stephanie Kleine-Ahlbrandt, the International Crisis Group’s North East Asia Project Director in Beijing in a recent article.

No comments:

Post a Comment